Deinonychus

Dinosaur

Reconstruction of Deinonychus

Deinonychus was a small, carnivorous theropod dinosaur that lived during the Cretaceous period, around 115 to 95 million years ago, in what is now the western United States - including Montana, Wyoming, and Utah. Currently, only one species is known: Deinonychus antirrhopus.

Discovery and Naming

The first remains of what we now recognize as Deinonychus were uncovered in the 1930s in Montana. However, the bones were jumbled and confused with those of other species. One skeleton was even misidentified as belonging to a completely different dinosaur, although a few of the teeth in the mix did belong to Deinonychus. It wasn't until the 1960s, when clearer fossils were discovered in Montana, that scientists realized they were looking at a distinct predator.In 1969, paleontologist John Ostrom carefully studied these new finds and officially named the animal Deinonychus antirrhopus, meaning "terrible claw," after the large, curved claw on each foot. His research revealed that this was no sluggish reptile, but an agile predator with bird-like features and signs of active hunting behavior. This discovery helped spark what scientists call the "dinosaur renaissance" - a major shift in thinking that overturned the outdated image of dinosaurs as cold-blooded, slow-moving reptiles. Thanks in part to Deinonychus, researchers began to view dinosaurs as dynamic, active creatures and close relatives of modern birds.

Physical Characteristics

Deinonychus was a medium-sized predator, growing to about 3.4 m in length, standing nearly 1 m tall at the hips, and weighing around 60 - 100 kg, depending on the individual. Its skull, roughly 40 cm long, contained powerful jaws with around seventy sharp, curved teeth. Forward-facing eyes provided strong depth perception for hunting. Each hand bore three long claws, while the feet carried the distinctive sickle-shaped claw on the second toe. This claw was held off the ground when not in use to keep it sharp. Its long, stiffened tail acted as a counterbalance - a trait referenced in the species name antirrhopus, meaning "counterbalancing."

Feathers and Relatives

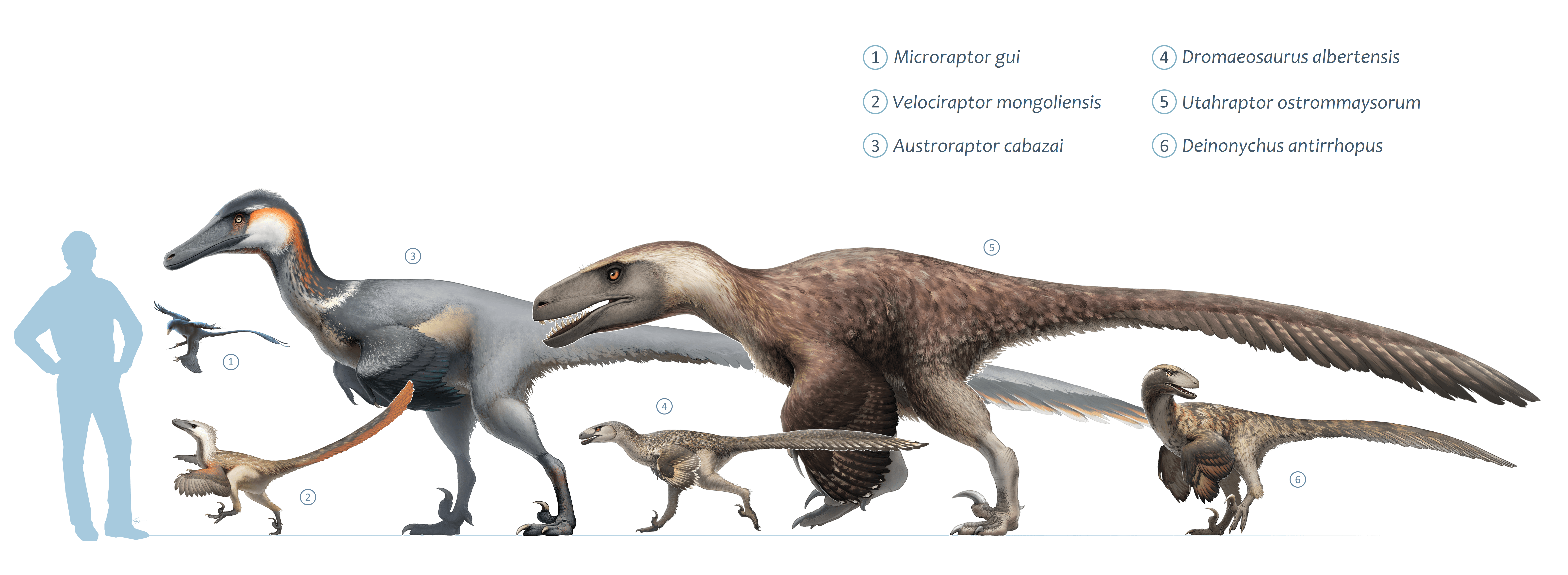

Although no skin impressions of Deinonychus itself have been found, strong evidence from close relatives suggests it was feathered. Fossils of related dromaeosaurs like Microraptor show fully developed, bird-like feathers on the arms, legs, and tail. Specimens of Velociraptor have preserved quill knobs on the forearm - direct evidence of wing feathers. Since all dromaeosaurs with known skin impressions had feathers, paleontologists are confident that Deinonychus was feathered as well.Deinonychus belonged to the dromaeosaur family - small to medium-sized predators known for their sickle claws and bird-like traits. In popular culture, these dinosaurs are often called "raptors," though the term isn't scientific and can be misleading. Some dromaeosaurs, like Velociraptor and Bambiraptor, include "raptor" in their names, while others like Deinonychus and Achillobator do not. Meanwhile, some dinosaurs with "raptor" in their names - such as Corythoraptor, an oviraptorid - are not dromaeosaurs at all.

The Sickle Claw and Hunting Strategy

Life restoration of Deinonychus pinning a Zephyrosaurus using the prey restraint model.

Deinonychus is most famous for the large sickle-shaped claw on each foot. Early studies suggested it might have used this claw to slash open large prey, but later research has cast doubt on that idea. Tests with life-sized models showed the claw wasn't sharp enough to cut deeply but was excellent for gripping or pinning struggling animals. The leading theory today - the "raptor prey restraint" model - proposes that Deinonychus hunted much like modern eagles or hawks: leaping onto prey, using its claws to hold it down, and beginning to feed while the victim was still alive. Its feathered arms may have helped with balance during the struggle, while the stiff tail stabilized its movements.

Scientists have debated how powerful the bite of Deinonychus really was. Early muscle reconstructions suggested a weak bite compared to other large predators. However, tooth marks found on bones of prey animals hinted that it could sometimes puncture bone. A detailed 2022 study using an actual skull estimated the bite force at about 706 newtons - far below the 13,000–15,000 newtons of a modern alligator. This suggests Deinonychus didn't rely on crushing power. Fossil sites often contain Deinonychus remains and teeth alongside bones of Tenontosaurus, suggesting it regularly fed on this dinosaur, whether through predation or scavenging.

Scientists have debated how powerful the bite of Deinonychus really was. Early muscle reconstructions suggested a weak bite compared to other large predators. However, tooth marks found on bones of prey animals hinted that it could sometimes puncture bone. A detailed 2022 study using an actual skull estimated the bite force at about 706 newtons - far below the 13,000–15,000 newtons of a modern alligator. This suggests Deinonychus didn't rely on crushing power. Fossil sites often contain Deinonychus remains and teeth alongside bones of Tenontosaurus, suggesting it regularly fed on this dinosaur, whether through predation or scavenging.

Speed and Movement

Although often imagined as a fast-running dinosaur, research shows that Deinonychus was probably not built for high speed. The key clue lies in the proportions of its leg bones. In animals adapted for running, like ostriches or the ostrich-mimic dinosaurs (Struthiomimus), the lower leg bones and foot bones are very long compared to the upper leg bone (the femur). This gives them a long stride and efficient movement at high speed. In Deinonychus, however, the lower legs and especially the upper foot bones (the metatarsus) were relatively short. The ratio of these bones to the femur is much lower than in true sprinters, meaning its stride would have been shorter and less efficient for running.Social Behavior

Illustration of Tenontosaurus

Fossil sites frequently show multiple remains of Deinonychus alongside the plant-eating Tenontosaurus, leading some scientists to suggest that it may have hunted in groups. In Montana and Oklahoma, several quarries contain multiple Deinonychus skeletons and Tenontosaurus bones mixed together. Since an adult Tenontosaurus could weigh several tons - far more than a single Deinonychus - John Ostrom and others proposed that only cooperative hunting could bring such large prey down. This idea helped form the popular image of Deinonychus as a pack hunter.

However, later studies have challenged this interpretation. Some scientists argue that the evidence may instead point to opportunistic feeding, more like modern crocodiles or Komodo dragons, which gather at carcasses but often fight among themselves and even cannibalize smaller individuals. Trackway evidence and isotopic studies suggest a more nuanced picture: Deinonychus was likely at least somewhat social, tolerating the presence of others while feeding. While there is no proof of wolf-style cooperative hunting, there is some evidence to suggest that Deinonychus was not a purely solitary predator either.

However, later studies have challenged this interpretation. Some scientists argue that the evidence may instead point to opportunistic feeding, more like modern crocodiles or Komodo dragons, which gather at carcasses but often fight among themselves and even cannibalize smaller individuals. Trackway evidence and isotopic studies suggest a more nuanced picture: Deinonychus was likely at least somewhat social, tolerating the presence of others while feeding. While there is no proof of wolf-style cooperative hunting, there is some evidence to suggest that Deinonychus was not a purely solitary predator either.

Environment and Ecosystem

Deinonychus lived during the Early Cretaceous in warm, wet environments of floodplains, forests, and swamps - landscapes similar to modern-day Louisiana. Fossils from the Cloverly Formation (Montana and Wyoming) and the Antlers Formation (Oklahoma) show it shared its world with armored dinosaurs like Sauropelta, small herbivores like Zephyrosaurus, and larger prey such as Tenontosaurus. In Oklahoma, the ecosystem also included giants like Sauroposeidon, the predator Acrocanthosaurus, crocodiles, and large fish like gars. If teeth found in Maryland are correctly identified as belonging to Deinonychus, it may also have lived alongside Astrodon and the armored Priconodon.In Popular Culture

In popular culture, Deinonychus is best known as the real dinosaur behind the "Velociraptors" of Jurassic Park. Author Michael Crichton consulted with John Ostrom while writing the novel and based nearly all the characteristics of his raptors on Deinonychus. However, he used the name Velociraptor because he thought it sounded more dramatic. The filmmakers followed suit, depicting dinosaurs with the size and shape of Deinonychus, not the much smaller real Velociraptor, which was roughly the size of a turkey. In fact, the movie version more closely resembled the larger Deinonychus - or even Utahraptor, a giant relative discovered shortly before the film's release.

References & Attributions

Image: Reconstruction of Deinonychus - Emily Willoughby, (e.deinonychus@gmail.com, emilywilloughby.com), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsImage: Life restoration of Deinonychus pinning a Zephyrosaurus using the prey restraint model. - Emily Willoughby (e.deinonychus@gmail.com http://emilywilloughby.artworkfolio.com/), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Size comparison of Deinonychus to a human. - No machine-readable author provided. Dinoguy2 assumed (based on copyright claims)., CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Deinonychus skeleton on display at the Field Museum of Natural History. - Jonathan Chen, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Design of the Velociraptor from the Jurassic World trilogy - RATSUEKWAU PTAMG 380, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Size chart of different dromaeosaurs compared to a human (click to enlarge). - Fred Wierum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Illustration of Tenontosaurus - Nobu Tamura (http://spinops.blogspot.com), CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons