Diplodocus

Its fossils are among the most common in the Morrison Formation, a rock layer known for its many large dinosaurs such as Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Brontosaurus. The name Diplodocus means "double beam" - referring to the unusual paired bones found beneath its tail that were once thought to be unique to this dinosaur.

There are currently three recognized species of Diplodocus: D. longus, the original and type species named in 1878; D. carnegii, described in 1901 from an exceptionally complete skeleton; and D. hallorum, a larger and geologically younger species first described in the 1990s.

Where It Lived

Diplodocus lived during the Late Jurassic period, around 150 million years ago, in what is now the western United States. At that time, the region formed part of the Morrison Formation - a vast basin where rivers flowing east from the rising Rocky Mountains deposited layers of mud, sand, and silt across broad floodplains, lakes, and river channels. The climate was warm and semi-arid, with distinct wet and dry seasons that brought periods of heavy rain followed by long spells of dryness. This landscape supported a diverse community of life: other large sauropods such as Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus, predators like Allosaurus, and plant-eaters including Stegosaurus and Camptosaurus. Smaller reptiles, early mammals, turtles, and crocodile-like animals lived alongside them, while pterosaurs glided overhead. The vegetation was dominated by conifers, cycads, ginkgoes, and ferns, with mosses and horsetails in wetter areas - an environment well suited to sustaining the giant herbivores of the Jurassic.

Discovery

After the Bone Wars, other institutions joined the race to find more complete sauropod skeletons. In 1897, the American Museum of Natural History uncovered a partial but well-preserved Diplodocus skeleton in Wyoming - the first significant individual of the genus to be prepared and later mounted for display. But the most famous discovery came two years later, when a Carnegie Museum team funded by industrialist Andrew Carnegie unearthed an exceptionally complete skeleton in Sheep Creek, Wyoming. Described in 1901 as Diplodocus carnegii, it became the model for the first full Diplodocus mount, affectionately nicknamed "Dippy". Carnegie financed casts of Dippy that were sent to major museums across Europe and South America, making Diplodocus one of the most widely recognized dinosaurs in the world and a symbol of early 20th-century scientific cooperation.

Size and Description

Its neck, composed of at least 15 vertebrae, allowed Diplodocus to browse across a wide range of vegetation without moving its massive body. It likely fed on soft ferns and leaves, using its narrow, forward-pointing, peg-like teeth to strip foliage rather than chew it. Though no skull has been definitively found attached to a Diplodocus skeleton, skulls of close relatives suggest it had a small, low head with nostrils set far back and a mouth adapted for combing through vegetation, pulling leaves from stems rather than chewing. Its braincase was likely tiny compared to its body, typical of sauropods.

The tail of Diplodocus was perhaps its most remarkable feature - a tapering structure of around 80 vertebrae that made up over half its total length. It likely acted as a counterbalance for the neck and helped stabilize the body, but scientists have long debated whether it had other uses. Earlier ideas proposed that the tail could crack like a whip at supersonic speed, producing a loud sound to startle predators or communicate with others. However, recent biomechanical studies suggest that such speeds would have damaged the bones and soft tissue, making this unlikely. A slower, defensive tail-swipe remains plausible, and a newer theory suggests the tail might have served a social or tactile role - brushing or lightly striking other individuals to maintain contact or signal within herds. Fossilized skin impressions also show small scales and even narrow, pointed spines along the back and tail.

Behavior and Activity

Because Diplodocus is known from so many well-preserved skeletons, scientists have been able to study almost every aspect of its biology in detail. Early paleontologists once imagined it as a slow, semi-aquatic creature that spent much of its time wallowing in swamps, supported by water. This idea came partly from the position of its nostrils high on the head, which seemed suited for breathing while submerged. But later research showed that the immense water pressure on the chest would have made underwater breathing impossible. Since the 1970s, studies have firmly established that Diplodocus was a land-dwelling herbivore, feeding among trees, ferns, and low vegetation.Comparisons of the eye bones, called scleral rings, suggest that Diplodocus may have been active in short bursts throughout both day and night - a pattern known as cathemeral behavior. Scientists study the ratio between the opening in the scleral ring and the overall size of the eye socket, which in living birds and reptiles correlates with how much light their eyes are adapted to gather. Species active mainly at night tend to have proportionally larger openings, while daytime species have smaller ones. The measurements for Diplodocus fall between these ranges, implying it could see well in varying light conditions and was probably active at intervals across the day. However, this method only gives clues about light sensitivity rather than behavior itself, so while the results are suggestive, they aren't definitive.

Breathing and Circulation

Like other sauropods, Diplodocus faced biological challenges due to its size, particularly in breathing and circulation. Its long neck would have created a large "dead space" of air that made breathing less efficient if it relied on a reptile-like or mammal-like system. Most scientists now think it had an avian-style respiratory system, with air sacs that extended into the neck bones and allowed a continuous flow of air through the lungs, much like modern birds. This would have provided the oxygen needed to sustain such a massive body. Its heart and blood pressure systems remain subjects of debate - some earlier models suggested the need for "auxiliary hearts" to pump blood up the long neck - but most researchers now believe that its largely horizontal neck posture minimized the problem.Neck Posture and Movement

That neck posture has been another area of shifting interpretations. Early reconstructions showed Diplodocus with its neck arched upward like a giraffe, but modern evidence suggests that its neck was usually held horizontally, supported by strong ligaments running from the back toward the head. This would have allowed it to sweep its head over wide feeding areas without expending much energy lifting it high. This posture appears to have been typical of Diplodocus and its close relatives, while other sauropods such as Brachiosaurus and Camarasaurus carried their necks more steeply, allowing them to feed from taller vegetation.Some biomechanical models suggest that Diplodocus could rear up on its hind legs, using its powerful tail as a prop, potentially reaching food several meters above ground. However, later research suggests that this would have been very energy-intensive and probably not something the animal did often. Most scientists now think Diplodocus fed primarily by moving its neck side-to-side at roughly shoulder height, occasionally stretching higher when needed but rarely, if ever, adopting a full rearing posture.

Feeding Behavior

Differences in tooth and jaw shape among Morrison Formation sauropods suggest that they fed on different plants at different heights, reducing competition. Juvenile Diplodocus had broader snouts and more extensive tooth rows, suggesting they may have fed on softer, low-growing plants - a natural form of niche partitioning between young and adult individuals.

Reproduction and Growth

Little direct evidence survives of how Diplodocus reproduced, but studies of related sauropods indicate that it probably laid small eggs in shallow pits, possibly communally, to reduce the risk of predation. Despite their giant size, sauropod eggs were relatively small and numerous, allowing quick incubation. Growth studies of bone tissue show that Diplodocus grew rapidly, reaching adult size within a few decades, though some individuals, like D. hallorum, may have continued growing slowly for much longer.References & Attributions

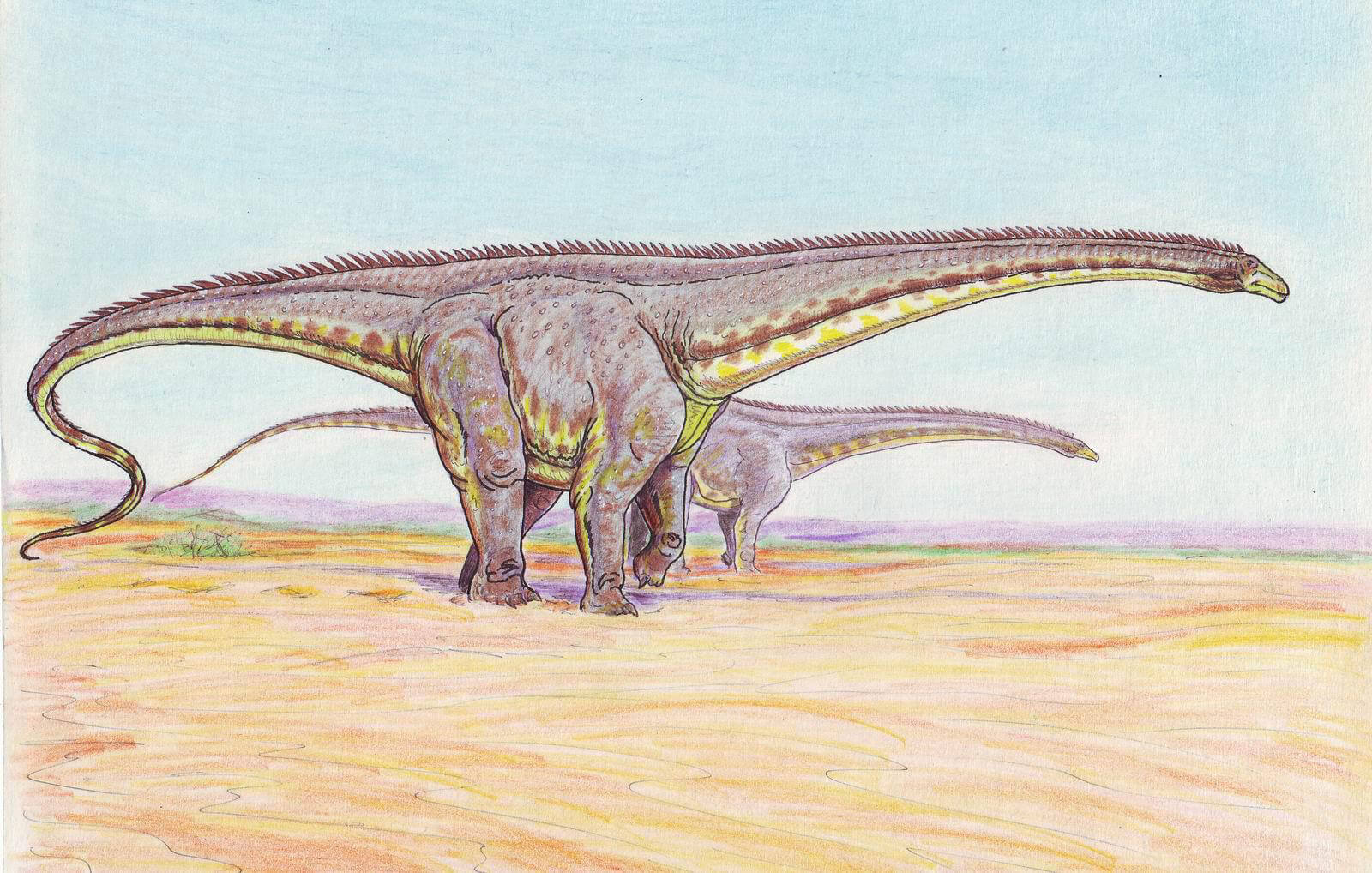

Image: Life restoration of Diplodocus longus - Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsImage: Diplodocus skeleton (nicknamed Dippy) at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History - ScottRobertAnselmo, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Sizes of two species of Diplodocus compared to a human - KoprX, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image: Reconstruction of a juvenile Diplodocus feeding with adults - Art by A. Atuchin. Published by D. Cary Woodruff, Thomas D. Carr, Glenn W. Storrs, Katja Waskow, John B. Scannella, Klara K. Nordén & John P. Wilson., CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons